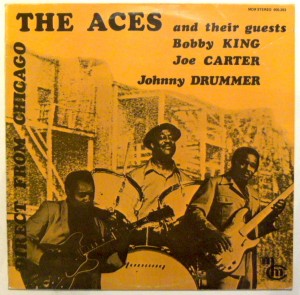

This article originally appeared in Living Blues magazine #205 in February, 2010. I had wanted to write it for years. The recordings made by Marcelle Morgantini in Chicago during the 1970s are a definitive evocation of the real blues of the day. Her recording of The Aces is one of my favourite albums.

Chicago Blues Box: Marcelle Morgantini and MCM Records

The blues changes lives. Ask any blues lover, and they will be able to tell you exactly where and how they first heard the blues. They will tell you who the artist was and the name of the album, or the radio show, or the friend who introduced them to the music. Some will even tell you the name of the label and when the session was recorded.

For Marcelle Chailleux Morgantini, a cultured young French woman from the wine-producing Loire region in central France, that moment came in 1953. She was working as a school teacher, in the town of Pau, near the Spanish border. It was the beginning of a journey that would take her to some of the toughest blues bars in Chicago, where she made a series of recordings that are worthy of a place alongside any of the most compelling moments in blues history.

Artists such as Magic Slim, Jimmy Johnson and Willie James Lyons all made their first blues albums for Marcelle Morgantini’s MCM label. Yet you will struggle to find references to the recordings in any of the standard blues discographies or biographies. An Internet search reveals little more than references to Marcelle as a producer on the CD reissues of her work, except for one tribute on a French jazz website: her obituary in 2007.

A combination of bad timing, limited funds and perhaps a little chauvinism – was there room in the 1970s for a French woman in an American man’s world? – seems to have consigned the MCM catalog to obscurity. Yet for anyone who could not be in the Chicago clubs at the time the recordings were made, they are a unique collection of authentic, unedited live performances. Some are by men who have since become giants of the blues scene, others by men who died leaving their MCM albums as the only record of their talent.

The story of Marcelle Morgantini’s dramatic conversion to the blues, and her commitment to helping undiscovered bluesmen get their first break in the business, is a fascinating study of the power of the blues.

Back in 1953, Marcelle attended a lecture given by Jacques Morgantini, one of the founders of the Hot Club de France. The Hot Club played a key role in bringing jazz and blues to Europe and Jacques was – and still is – a passionate evangelist for the music.

He played his 78 of Muddy Waters’ “Honey Bee” at one of his jazz and blues appreciation lectures in Pau, as well as Sidney Bechet’s recording of “Gone Away Blues”.

Jacques, a sprightly 81-year old who still lives in the house he and Marcelle built in Gan, near Pau, vividly recalls his first encounter with his wife-to-be: “She came to me and she said, ‘I only know classical music; I did not know it was possible to get so much emotion from this music. It is absolutely marvellous. Where can I buy this music?’”

In the years that followed, Jacques mentored Marcelle on her journey into the blues. “She had an excellent ear for jazz, but her real love was blues,” he says.

“We married in 1963; it was impossible for me to have a wife who did not love jazz and blues. In all our years together, she was a great help to me in my work for the Hot Club de France and the Black and Blue label.”

Jacques Morgantini remains a central figure in the history of the blues in Europe. He worked as a salesman for an electrical company, but he devoted all his spare time to promoting jazz and blues to the European fans who were just discovering the music of black America.

This included bringing many artists over for their first tours of Europe, including Big Bill Broonzy in 1951. “He came to stay at my parents house in Pau for a week,” recalls Jacques. “At that time, we were still learning about the blues in Europe, it was very hard to find information. I said to Big Bill, tell me about this group, these Muddy Waters people. He said, ‘This is not a group, it is a guy, McKinley Morganfield.’ This is how little we knew in those days.”

It was only a few years later that Muddy Waters himself came to stay, headlining Jacques’ series of concerts under the banner of The Chicago Blues Festival. During the 50s and 60s the festivals featured a who’s who of blues legends, among them John Lee Hooker, T-Bone Walker, Memphis Slim, Johnny Shines, Koko Taylor and Jimmy Rogers. Jazz greats such as Count Basie and Lionel Hampton also got the full Morgantini treatment when they came to Europe.

After their marriage, Jacques and Marcelle entertained these giants of black American music at their charming single-storey home in Gan. Jacques’ collection of home movies includes footage of The Aces – Dave and Louis Myers and Fred Below – jamming in the living room with Luther Johnson, Jimmy Rogers and Lonnie Brooks.

Jimmy Dawkins was also a regular visitor, during trips to record albums for the Black and Blue label. His Tribute To Orange, now available on Evidence, includes “Marcelle Morgantini’s Cassoulet” and “Marcelle Jacques et Luc”. Marcelle and Jacques’ son Luc, a boy born into a world of blues, later accompanied her on her trips to Chicago.

Over the years, the Morgantinis became close friends with many of the musicians, in particular Jimmy Dawkins and Fred Below. Eventually, the time came when Jacques, Marcelle and Luc made the trip to Chicago to see the music they loved being performed on its home territory.

“Jimmy and Fred had told us that that there were many excellent blues players who had not been recorded,” says Jacques Morgantini. “We wanted to see them for ourselves, in case they could record for Black and Blue, or could come over for the Chicago Blues Festival tours.”

So it was that this smart French family – Jacques complete with the definitive Frenchman’s black moustache and mischievous eyes – arrived on the South Side of Chicago in the early 70s, with Fred Below, Jimmy Dawkins and singer Andrew “Big Voice” Odom as their guides. For an American blues fan, it would be a dream come true. For a European fan, it was beyond a dream.

Marcelle and her family visited the clubs where the hard, urban blues was still being played. Venues like Ma Bea’s, The Golden Slipper, Theresa’s Lounge and the 1125 played host to blues celebrities such as Junior Wells and Carey Bell, alongside men who were still largely undiscovered, such as Magic Slim, Eddie Clearwater, John Littlejohn and Bobby King.

“We came to one club that was like a disused warehouse, with a chicken wire fence all around it,” says Jacques. “Fred Below was with us. I walked in and it was like John Wayne walking into a bar in an old Western movie. The band stopped, and maybe 30 black faces turned towards me. I felt like the only white man for miles at that moment. Suddenly I realised that Below and the others were not behind me – I had walked in on my own. I was like the French army – I retreated back out the door, to find Below on the sidewalk talking to a friend.”

In February 1975, Marcelle journeyed again to Chicago, in the company of Jean-Marie Monestier, founder of the Black and Blue label. Monestier was a great help to Marcelle in the early stages of the project. His knowledge of the logistics and the business side, as well as the credibility of the Black and Blue name, were crucial to the initial success of MCM.

Marcelle returned from her Chicago pilgrimage filled with excitement at what she had seen. She was determined to help the blues players who were struggling to make a living, doing menial work by day, playing for a few dollars in the neighbourhood clubs every night.

Says Jacques Morgantini: “It was the year of Marcelle’s 50th birthday and she came into some money from her family. She said to me, ‘I do not want an expensive coat or jewels – I want to go to Chicago to record the blues’.

“This was deeply important to her and she knew that it could only be done if she had her own record label. She wanted complete artistic control, so she could capture the blues in Chicago the way she saw it and heard it.”

Drawing on years of producing sessions for Black and Blue, Jacques gave his wife and son a crash course in recording live music and equipped them with a Nagra IV-S tape recorder – the state-of-the-art among portable recording machines of the day. Marcelle and Luc flew to Chicago, where Jimmy Dawkins met them at O’Hare airport.

“The blues at that time was still going pretty good in Chicago,” says Dawkins. “There was a lot of clubs and lots of bands playing to black audiences on the South and West sides. This was just after the time of Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, so it was still pretty popular.”

However, the wider market for recorded blues was moving from a mainly black audience to a mainly white audience, who were picking up on the roots of rock music. Jimmy Dawkins acknowledges that live blues was beginning to follow the same migration from black to white audiences when Marcelle arrived.

“We was beginning to play the white-owned clubs like Kingston Mines on the north side of town,” he says. “This is where a lot of the work is today. I guess Marcelle arrived just in time to capture the last days of the old-style neighborhood clubs. Places like Ma Bea’s, Theresa’s and the old Golden Slipper are all gone now. So it was good to have someone interested enough to come and to hear us play and record us, and to try to make us known more to the world. That was great.”

Marcelle arrived with their Nagra machine, a small mixing desk and a selection of microphones. With almost no personal experience of recording anything, let alone loud electric bands, she plunged into the South Side in search of the blues.

The first date was with Homesick James; Marcelle was due to record him at his home. One of her American contacts had been tasked with bringing some microphone stands for the session, but arrived without them. He went back for them, but by the time he returned the musicians had enjoyed a little too much of Homesick’s generous hospitality. The session was a failure.

“It was a hard introduction to the real business of recording the blues,” says Jacques. “Marcelle was inexperienced in working with musicians in this way and she did not get another opportunity to record Homesick James.”

Marcelle’s next sessions were more successful. She recorded Willie Kent and Willie James Lyons at Ma Bea’s, followed by The Aces with special guests Bobby King, Joe Carter and Johnny Drummer.

She and Luc also travelled to the Queen Bee to catch Bobby King in his own right. The recordings were made in the afternoons and early evening, before the noise of the audience could become too intrusive.

Says Jimmy Dawkins: “It was natural and for real without over preparation. You get the feeling of the room, the music, the audience and the blues. It was the real thing.”

Bobby King’s album Chaser proved to be his only full-length recorded work. By the time Marcelle returned the following year, keen to record him again, King had died of a heart attack.

Many of the artists who made their first blues albums for MCM went on to lasting fame. Jimmy Johnson credits Marcelle Morgantini as the first person to give him a chance as a bluesman.

“The American labels saw me as a soul player,” he says, “because I was working with my brother Syl. Marcelle was good to me and wanted me to record a blues album to help me establish myself on the blues scene. My MCM albums, Tobacco Road and Ma Bea’s Rock, helped me get recognised by the big blues labels.”

For Marcelle Morgantini, however, the main priority for her first recording trip was Magic Slim.

“Slim was working at a laundry during the day, and earning small amounts for gigs at night,” says Jacques Morgantini. “Marcelle was upset that a man with such talent should not have the recognition he deserved.”

The bandleaders were paid $400 for each session, with $200 for each sideman. At the end of Magic Slim’s session for his first album, Born On A Bad Sign (sic), the guitarist disappeared into the men’s room with his cash. Luc followed him in, and found him staring at the money.

“I had never had that much money at one time,” recalls Slim. “Marcelle was the one who recorded my first full length albums. I had a young family and I was working in the laundry Monday through Friday, and playing Friday, Saturday and Sunday night.

“But the record I made for MCM was the one that got me started. About a year after recording for Marcelle, I was able to go full time with my music – and they still working the hell out of me now!”

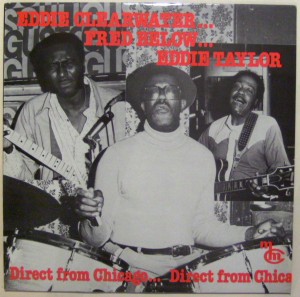

Marcelle made three more trips to Chicago, recording albums by Jimmy Dawkins, Andrew “Big Voice” Odom, Big Mojo Elem, John Littlejohn, Hip Linkchain, Andrew “Blueblood” Mac Mahon and Eddie Clearwater. Two albums of jam sessions were also issued, featuring appearances by Eddie Taylor and Junior Pettis alongside the stalwarts of the MCM roster, Dawkins, Johnson and The Aces.

Like Bobby King, the album with Willie James Lyons proved to be the only full length recording made by the guitarist before he was killed in a knife attack. Hip Linkchain died of cancer with few other recorded works to his name. Their MCM recordings are vital documents of major talents, who may otherwise have passed without acknowledgement of their role in taking the blues to a new generation of listeners.

Sadly, Marcelle’s funds were limited and she was unable to promote her catalog to compete with the recognised blues labels. The MCM project finally came to an end as a recording business in 1978. The sales of MCM recordings may also have suffered from the decline in mainstream interest in the blues that took place in the 1970s. Marcelle’s recordings were made after the 60s blues boom, and had fallen into obscurity by the time Robert Cray and John Lee Hooker led the blues revival in the 80s.

A new chance of success came when Karl Emil Knudsen, from the Storyville record label in Denmark, made an offer to Marcelle for the rights to release the recordings on CD. A deal was struck, and most of Marcelle’s work is now available on the Storyville label, including many of the tracks that did not make it onto vinyl. Still, however, the MCM catalog remains largely ignored by the blues mainstream.

Yet this is a remarkable body of work, not only for the moment in blues history that it captures, but also because of the quality of the sound and the unique character of the performances.

The blues was in transit at the time these recordings were made. In the work of Jimmy Dawkins, Magic Slim and Willie James Lyons, you can hear the seeds of blues-rock being sown. At the same time, there is much to bring joy to the hearts of Chicago traditionalists, with Fred Below and Dave Myers laying down the irresistible swing that propelled Little Walter, Junior Wells and others to lasting fame. The MCM album The Aces And Their Guests is arguably the definitive recorded work by the definitive Chicago blues band.

Jacques Morgantini is an unashamed maverick among producers and he passed his stripped down, warts-and-all approach on to Marcelle and Luc. The simplicity of the recording technique, in which the ambience of the venue is captured alongside the sounds of the instruments, gives a warmth and honesty to the sound that eludes most modern engineers. It is a sound that has divided critics over the years, but for many lovers of the blues it is the nearest they will ever get to actually being in a Chicago club when the classic performers were still doing their thing.

And then there are the performances themselves, with the inheritors of the urban blues tradition demonstrating its depth and beauty with impassioned, majestic power. Many of the tracks are extended jams, allowing the instrumentalists to give full expression to their talents. You have the savage bite of Magic Slim, the sparse intensity of Jimmy Dawkins, the jazzy lilt of The Aces, the raucous joy of Mojo Elem, the funk and swing of Bobby King.

Although Marcelle Morgantini did not live to see it, her influence on the new generation of Chicago blues players is profound. Nick Moss, former sideman for Jimmy Rogers and now leading his own band, the Flip Tops, recognises the MCM catalog as one of the essential ingredients that helped to shape his sound.

“I heard Bobby King’s Chaser album just about the time I first started playing the blues,” he recalls. “Then I got the Hip Linkchain album, I’m On My Way, and that completely blew me away. I had seen Hip Linkchain playing live and for me this was the album that really captured what he was about.

“Studio recordings can often sound really restrained, but live recordings like these, there’s no hiding place. You have to put yourself on the line, and the MCM recordings capture the artists doing just that. They sound like the blues as I heard it for real.

“For me, there’s only a few labels that really capture that live sound of the Chicago blues, like the early Vanguard and Chess studio recordings, and the MCM recordings made by Marcelle. When I’m recording, I want it to sound like you’re sitting in the audience listening to the band, and I have that raw MCM sound in my mind. It is what it is; just some guys in a bar playing the blues.”

With Marcelle’s work helping to shape his own fresh sound, Nick Moss is taking her influence forward, ensuring its place in the evolution of the blues. And, as if to complete the story that began with Marcelle’s recordings of Magic Slim, Slim’s latest album, Midnight Blues, is produced by Nick Moss.

The MCM recordings are a vivid testimony to depth of Marcelle Morgantini’s passion and determination to help the blues players she loved. She was simply a blues fan, but one who was lucky enough to have the resources and the contacts to turn her love of the music into a legacy to be shared with her fellow fans all over the world.

In August 1978, Jimmy Dawkins wrote to Marcelle from California. His words show how much her work meant to the bluesmen of Chicago:

“Marcelle dear, you have done a good thing working with the black blues artists. They look each year for the lady to come from France. They sometimes say to me, ‘When is the lady going to get here from France that makes the records?’ because they do not know your name. All of them know that they cannot be recorded, but you give them hope, that someone does care.”

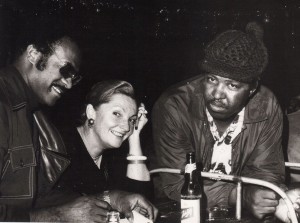

Marcelle Morgantini died in 2007, at the age of 82. Her presence is still strong in the house at Gan, with her collections of owl sculptures and books on Ancient Egyptian history, set between Jacques’ unique gallery of photographs of the jazz and blues greats. And she is there in the movies, laughing and joking with the giants of the Chicago blues as she serves them with her legendary cassoulet.

First published in Living Blues #205, Feb 2010